How the first foot clinics offered free healthcare to those in need

A century ago, universal access to foot care relied on the goodwill of clinicians and public donations

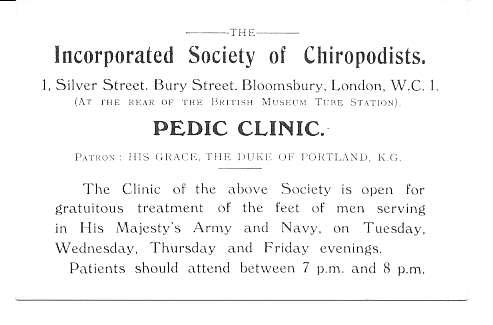

In 1913, the Incorporated Society of Chiropodists secured premises in London and opened the Pedic Clinic. Thirty-five years before the NHS was founded, it offered free foot care to those who could not otherwise afford it. The clinic was only open in the evenings, as staff worked in their private practices during the day to earn a wage.

The clinic was for ‘people whose living depended almost entirely upon the use of their feet,’ Dr A W Oxford, the clinic’s treasurer, wrote in a pamphlet published circa 1920.

‘Postmen, police constables and work girls of all kinds brought their troubles to the clinic and in a large number of cases it seemed astonishing that they could walk at all. Soon it was discovered by the clinicians that the average attendant was in a far worse condition than patients seen by them in their private practice.’

But running free services did not come cheaply. Expenditure in 1919 was just over £405 – almost £27,000 in today’s money – at a time when a factory worker might take home wages of less than £3 per week (around £200 today). The Pedic Clinic relied on donations to keep its vital services running, raised through benefit concerts, whist drives and generous benefactors. In 1919, over £338 was raised through donations and subscriptions – though this still left a substantial deficit. By 1920, expenditure reached over £522, but only £267 was raised.

A handwritten letter to a subscriber, dated 1923, survives in the College’s archive. ‘I venture to remind you that your valued subscription of one guinea has fallen due,’ it begins. (A guinea was one pound and one shilling; around £50 today.)

‘Your kind help is more than ever necessary – the number of patients is largely increasing, and funds are most urgently required to assist in carrying on the good work. Thanking you for your last support – which we would implore you not to discontinue, for the sake of those whose livelihood depends upon their treatment in the Society’s clinics.’

The Pedic Clinic during World War One

With the outbreak of war, the clinic opened its doors to treat Britain’s troops. Pamphlets declared the clinic ‘open for gratuitous treatment of the feet of men serving in His Majesty’s Army and Navy, on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday evenings. Saturday from 6-7pm is reserved for men on weekend leave from the provinces’.

Between 1913 and 1919, over 24,000 treatments were carried out, of which nearly 11,000 were on soldiers. Demand only continued to grow as the war went on, and in 1918 alone 4402 patients were seen.

The clinic’s president also trained battalion chiropodists: medics who were stationed on the front lines and could treat patients in situ. The authors of The Chiropodist, the Society’s journal, wrote in October 1916: ‘This form of service is, we think, a very practical help, as its results reach those whom we cannot attend personally.’

The clinic’s own staff were also called to fight, including registrar William Scherf, who joined the London Field Ambulance – part of the Royal Army Medical Corps – in 1916.